From Borneo I flew to Timor-Leste via Darwin. Unfortunately in the latter stages of the trip a nasty virus had run through the students, and I had come down with it myself. It was just your typical sinus infection – bit of nausea, very blocked nose, etc. I then discovered first hand just how bad flying with a sinus infection can be – the pressure in my sinuses was unable to find equilibrium during the descent into Darwin, leaving me thinking my eyeball was going to burst, or my ear. As a result I missed my connection to Dili, and instead went to emergency in Darwin. They told me they had both good news and bad news – my eardrum was bruised but not perforated. A perforated eardrum would have been very unpleasant, but it also would have made further flying safe, as I would have had no trouble equalizing!

After a day of rest in Darwin, and taking a lot of pre-emptive decongestants, I risked the flight to Timor-Leste. I was met at the airport by my student Jotham Lay, who was undertaking his final year project with me in humanitarian engineering. Jotham had designed, purchased, and had delivered the components of a grid-solar hybrid system for installation at the Leublora school in Maubisse, Timor-Leste. My colleague Dr. Sara Niner from the Monash School of Social Sciences has a long-standing relationship with the school, and we were working with Sara and other anthropologists from the Faculty of Arts on this project. Jotham was accompanied by his parents, who had volunteered their time for the trip, both having grown up in Timor-Leste. The project would likely have failed at the outset if not for the very generous support of his parents, who used their contacts to help us arrange transport, accommodation, helped us procure material, etc.

We were immediately confronted with one of the most stereotypical challenges in development work – delays in the arrival of equipment and material. We had been promised our material would be ready before we arrived, we instead found out we could not even get access to it until after we were supposed to fly home. After much wrangling over the phone, we managed to get a “compromise” negotiated, whereby we could get access to it three days before we were supposed to leave. The project timeline had just become rather compressed.

We drove out to have our first in-person inspection of the target site, the Leublora Green School:

The school is located in the village of Maubisse:

Though Maubisse is only about 70km from Dili, the drive takes many (hair raising) hours. After convincing our drivers that taking blind mountain corners at 130kmh (when most of the locals walk on the road) was not acceptable safety practice, we gritted our teeth and made it the rest of the way. The roads are very rough and poorly maintained, though we were relatively fortunate that they were usable at all. Rain can get so severe in Timor-Leste that many of the roads periodically flood completely.

Though it was a reasonably stressful drive, we made it to the school in the end. The school is as beautiful and peaceful as this picture would imply, however our period of relaxation was sadly short lived. We immediately discovered that the information we had been provided about power usage in the school was very inaccurate – always one of the dangers of attempting remote design. We had not been told about the existence of a hot water system and high-intensity flood lighting, which between them more than quadrupled the peak power draw on our system. This was not only impractical, it was unsafe. After recording as much information as we could, we headed back to Dili to plan.

With help from Jacob, Jotham’s father, and an experienced electrical engineer, we devised a new, much more complex wiring scheme to try to circumvent the hot water system (leaving it running exclusively on grid power). We also planned to replace all the safety floodlights with equivalent LED systems, to reduce the power draw there. This new system required us to purchase a lot of componentry in Dili. While one might assume that basic electrical supplies would be cheaper in a developing nation like Dili, they were significantly more expensive than in Australia. This unexpected cost ate up most of the project budget in one go.

Once we had purchased all our components, sat down and made detailed plans as best we could, we found that we had two days where nothing could be done – we were still not being given access to all the equipment we had shipped from Australia, and not much could be done on the weekend. We took some time to explore the coastline near Dili, which is truly beautiful:

While this period of time was pleasant, it was difficult to relax knowing the difficulties that still lay ahead.

We finally had the chance to unload the shipping container where our equipment had been sitting, untouched and unused, for days. The scene was chaos, at least five or six different groups had material in the container, and were all there to collect it.

We had organized for our technicians to meet us there at 9am to start transferring equipment immediately. They did not arrive until midday, which resulted in us getting yelled at by the operator of the shipping business, as well as getting increasingly stressed about our own project timeline.

We reached Maubisse at about 3pm in the afternoon, with only two full days ahead of us to complete the installation. We had hired three technicians from the National Centre for Employment and Professional Training (CNEFP), who had experience in solar installation. The work ethic displayed by these guys was incredible; they worked fourteen to fifteen hours per day without complaint, and had to be pestered into taking breaks for meals.

We got straight to unloading the truck, but so little daylight was left that not much was achieved on the first night. We arose early the next morning, and set to work. Our technicians were, in addition to being very hard working, highly skilled, and also very patient in putting up with our incessant micromanagement (even though they typically knew better than we did what had to be done). We did tend to butt heads on one particular point – safety.

The technicians had told us they all had safety harnesses when we first met in Dili. Once we arrived on site and they started getting ready to get on the roof, we asked where their safety harnesses were, only to hear “Back in Dili”. We kept pushing for more care to be taken, which resulted in many exchanges such as “Guys, in Australia, Safety is Number One”, only to be told “This is Timor, Safety is not number one!”. We eventually found a happyish medium, and the system rapidly took shape:

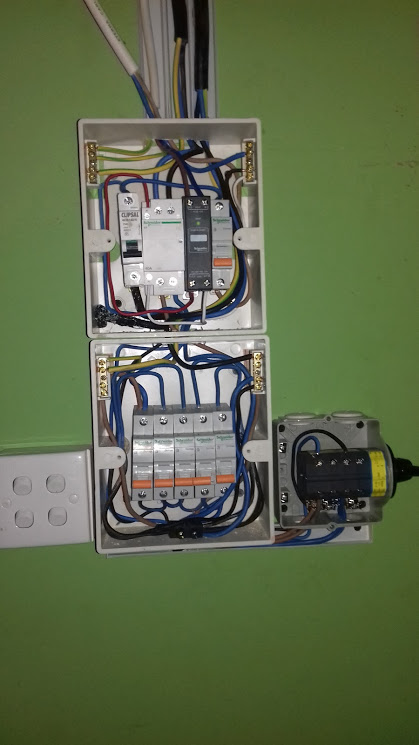

In an attempt to make the system as user friendly as possible, we had gone for a setup that was difficult to install, but easy to operate. The internal wiring and programming of the system was extremely challenging:

Towards the end though, despite all the language barriers and the complexity of the system, it did seem like it was all going to work. We started celebrating, but perhaps a little too early:

Unfortunately at the end of the very last day, we had one single component left to configure – an automatic switcher between the grid and the panels, so that the school would always have power. We made an error with the wiring diagram, and in the ensuing attempts to diagnose it, a short caused a system-wide failure, destroying the single most expensive and heavy component in the system. At this point we were still many hours drive from Dili, it was dark, and our flight left in twelve hours. It was a miserable experience.

Early on we had put in manual switches to make sure that no matter what happened, the school would still be operational and in better condition than we found it. This failsafe proved critically important, as it allowed us to leave with no dimunition of the school’s capabilities. The school remained on grid power, with much safer wiring, and a huge reduction in power usage from the installation of LEDs. However, solar power would not be available until the inverter could be shipped back to Australia, repaired, shipped back to Dili, and reinstalled. This is still in process, and hopefully the whole system will soon be operational.

Amongst the many lessons learned, was that we should have involved CNEFP not just in the installation, but the design. Their technicians were extremely skilled, but we chose equipment with which they were entirely unfamiliar. Compounded by the language barrier (we only had limited translator access), this eventually lead to project failure.

As heartbreaking as the end of the trip turned out, I was, and remain, very proud of all that Jotham achieved. With no prior background in the discipline, he setup and project managed a very complex endeavour in a difficult environment, that bar one poor choice in the eleventh hour, would have succeeded.