In June I had the opportunity to work with Engineers Without Borders as an Academic Mentor on their Humanitarian Design Summit program. The HDS is a fantastic initiative run by EWB, where engineering students from Australia can visit a developing nation to receive both training and hands-on experience in the practice of humanitarian design.

Engineers Without Borders takes the programs very seriously – they are not “voluntourism”. Students don’t show up, build a house, then leave again. The focus of the program is about learning to work with a community; learn their strengths, try to understand a bit about their lived experience, then seek to make a contribution with the skills and knowledge that you may have.

This year I was part of a mentoring scheme in the group’s first summit held in Sarawak, Borneo. For the first week we were based out of the capital city of Kuching, which is quite developed, with a generally high standard of living.

Here the students took various classes from the EWB mentors, focusing on humanitarian design principles, cultural sensitivity, appropriate technology, and some introductory classes in the local languages. This always involves confronting a lot of preconceptions about the nature of the work, and your role as an engineer in a developing community. EWB brought a diverse group of mentors, with expertise in engineering, education, gender equity and disaster relief.

After the training period in Kuching, we separated in to three groups, and departed for a week living with a community. Our group of students (Team Hornbill), went to live with the Land Dayak in Kampung Kiding. Kiding has only had a semi-usable road installed in the last few years, which means it was necessary to hike for several hours up a rather steep climb to get there:

Of course, some of us were smarter about packing light than others:

The hike wasn’t an easy one in the heat, but at the top we were greeted with our first sights of Kiding. This was a little more confronting than arriving in Kuching, which looked basically like an Australian city. Kiding is far less “developed”. They had had running water for a few years, a road has just been built, and they have only generator power as a periodic luxury.

Fortunately I was working with a very experienced team of mentors/facilitators, led by the irrepressible Captain Joli, who has run numerous design summits. Vivian Chordi, a specialist in gender equity in development, also had extensive experience working in developing nations (leaving me as the odd one out, experience wise).

Working with Joli and Vivian was one of the highlights of the experience. Both highly competent, warm and lovely people. Joli immediately settled the group in, and did her best to combat the onset of culture shock (which even I was feeling a bit, at this point). Acting as translators and guides, we also had Abby and Dawson, a husband and wife team who run sustainability focused tours to Kampung Kiding through their company, Backyard Tours. We were sharing meals and accommodation with our hosts, who were also putting up with us coming around asking incessant questions about their lives during the day.

Everyone in Kiding works as a farmer, though they harvest cash crops of pepper and chilli more than food crops (though rice is also harvested). The farming is demanding work – Kiding is so mountainous that the farms are all on steep slopes.

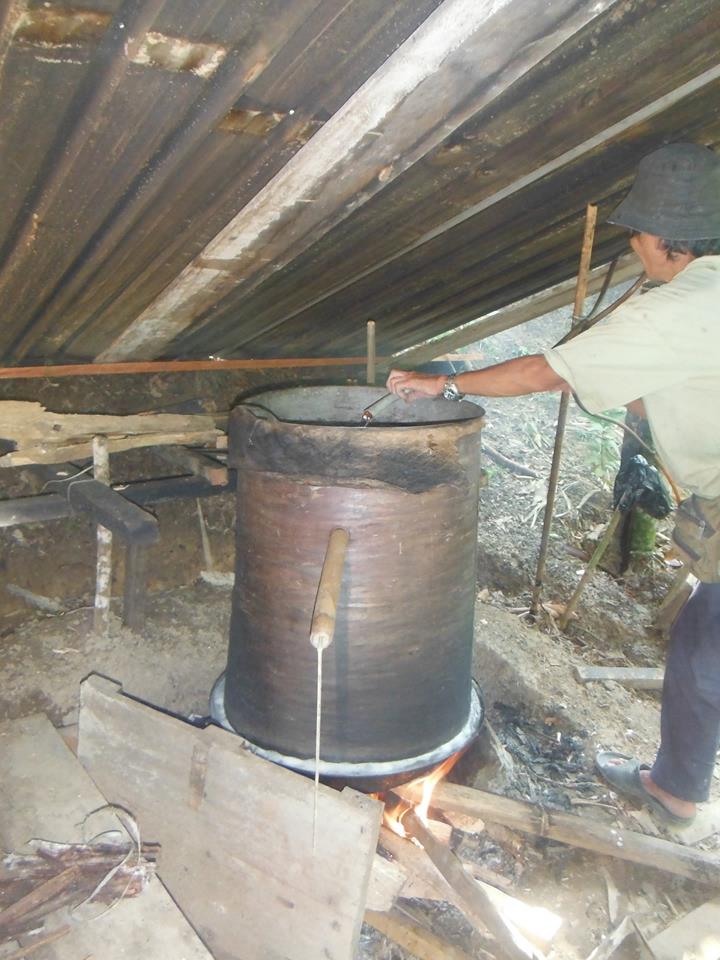

Babai Brendan, a local elder, took us under his wing and showed us his farm, as well as his proudest invention, a homemade distillery for producing liquor out of palm sap:

The design of the system was ingenious, using local materials and showing a deep understanding of some fundamental engineering principles. At this point, many of the students (and myself!) had a crisis of confidence. The level of basic know-how on display with the still seemed to suggest we would have little to offer in terms of knowledge transfer!

Continued in Part 2…